Book: Small Country by Gaël Faye

Context

While looking for a book for Burundi, I found that Small Country was recommended time and time again. The author’s name rang a bell, but I couldn’t remember from where. He had no other books!1 Turns out, he’s an artist I’ve been listening to for years. I am obsessed with him and you should all give him a listen while you read the sixteenth (!!) installment of this Read Around the World Challenge.

The Kingdom of Burundi, ruled by the Ganwa monarchs, has existed either as an independent state or under some version of European control since the 1600’s. The main ethnic groups, the Tutsi, the Hutu, and the Twa, have lived in the area for at least 500 years. Before diving in, below is a basic outline of Burundi’s changing political landscape after the Berlin Conference saw Africa carved up by European powers:

Independent state (1680–1890)

Part of German East Africa after the Berlin Conference (1890–1916)

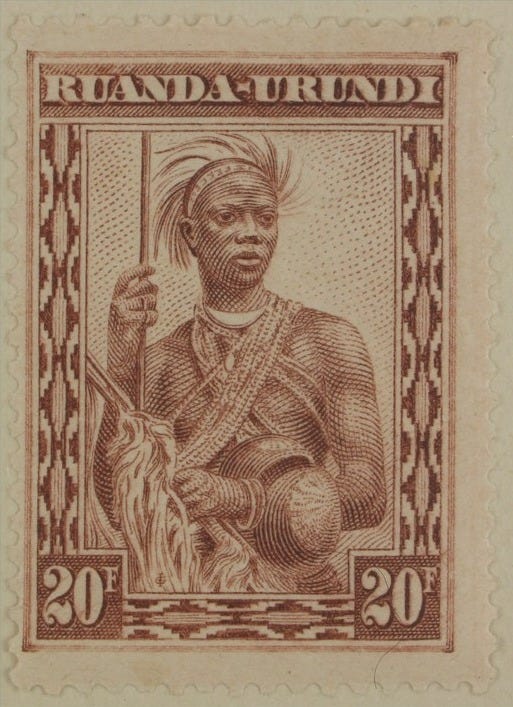

Part of Ruanda-Urundi, under Belgian military occupation (1916–1922)

Part of Ruanda-Urundi, under Belgian control according to a Class B League of Nations mandate (1922-1946)

Part of Ruanda-Urundi, under Belgian control according to a UN Trustee Agreement (1946-1962)

Independent state, Kingdom (1962–1966)

Burundi (1966-present)

Unsurprisingly, the history of Burundi and the other countries making up Africa’s ‘Great Lakes’ region are very closely intertwined - not only with the neighbouring Rwanda, but also with what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Tanzania. One country’s story can barely be told without the context of the others.

During World War I, the brutal Belgian army that occupied what was ironically called the ‘Congo Free State’ invaded modern day Burundi and Rwanda and began controlling the area under military occupation. After the war, Belgium was officially given control of the territory under a League of Nations mandate which eventually became a ‘Trusteeship Agreement’ in 1947 after World War II when the United Nations replaced the League of Nations.

Later on in 1962, the Trusteeship Agreement that had been put in place for Ruanda-Urundi was terminated and created Rwanda and Burundi. The resolution that dissolved the Trusteeship Agreement called for the countries to “emerge as two independent and sovereign States” and demanded the Belgian government to “withdraw and evacuate its forces still remaining in Rwanda and Burundi.”2

In the years following their independence, Burundi saw aggravated ethnic tensions that led to multiple coups. By the time Michel Micombero staged his own coup in 1966, establishing a military dictatorship and abolishing the monarchy, many politicians had been victims of political violence. Jean-Baptiste Bagaza followed in 1976, Pierre Buyoya in 1987, and then Pierre Buyoya again in 1996, in the midst of the Civil War. Are you still with me?

I would be remiss not to mention the role that Belgium and France played in exacerbating ethnic tensions for their own gain, supporting coups that would have their interests at the forefront and propping up rebel groups that were emboldened to perpetrate insane violence with impunity. They provided arms and military training, yet failed to mediate or act when needed. 3

In Small Country, we find ourselves in 1992 - on the verge of the Burundian Civil War that ravaged the country for more than a decade. The first multi-party elections the country ever held took place in 1993 between two-time coup leader Pierre Buyoya (a Tutsi) and Melchior Ndadaye4, the eventual winner and first Hutu leader of Burundi. Throughout this book, we experience the repercussions of this historic election through our narrator, Gabriel.

About the book

Small Country broke my heart. Even as I write this and think about what I want to say, I can feel a fist tightening over my heart and tears swelling up in my eyes. I have read many, and often graphic, accounts of numerous tragedies perpetrated across the globe, but something about experiencing it through the eyes of our 10 year old narrator, Gabriel, offered an entirely new dimension to the violence and suffering that was inflicted.

A child of colonialism — born in Burundi to a French father and an exiled Rwandan mother — Gabriel embodies the displacement that stemmed from years of complicated geopolitical relations. In 1992, Burundi and Rwanda found themselves on a path of genocide and dehumanization that led to massacres all across the country. Even Gabriel’s privileged existence as the son of a white French man is quickly flooded by violence.

“War takes it upon itself, unsolicited, to find us an enemy. I wanted to remain neutral, but I couldn’t. I was born with this story. It ran in my blood. I belonged to it.” -pg 109

Small Country’s account is lyrical, unforgiving, and raw. Every page of this book erodes at Gabriel’s childhood and forces him to confront the brutal reality that surrounds him. For most of the book, he refuses to see what is happening, he “wanted to make a fortress of [his] happiness and a chapel of [his] innocence”. When his surroundings eventually penetrate his fortress, he and his sister are sent to France when the violence becomes inescapable.

At this point in the book, Faye explores the lasting effects of trauma, as we hear from Gabriel as an adult in France, unable to move on from the wounds of his past and the collapse of his family. After his mother braves a return journey to Rwanda after the 100 days of genocide, she comes home a broken woman, unable to move past everything she witnessed. Gabriel writes that “genocide is an oil slick: those who don’t drown in it are polluted for life.”

Beyond the Book

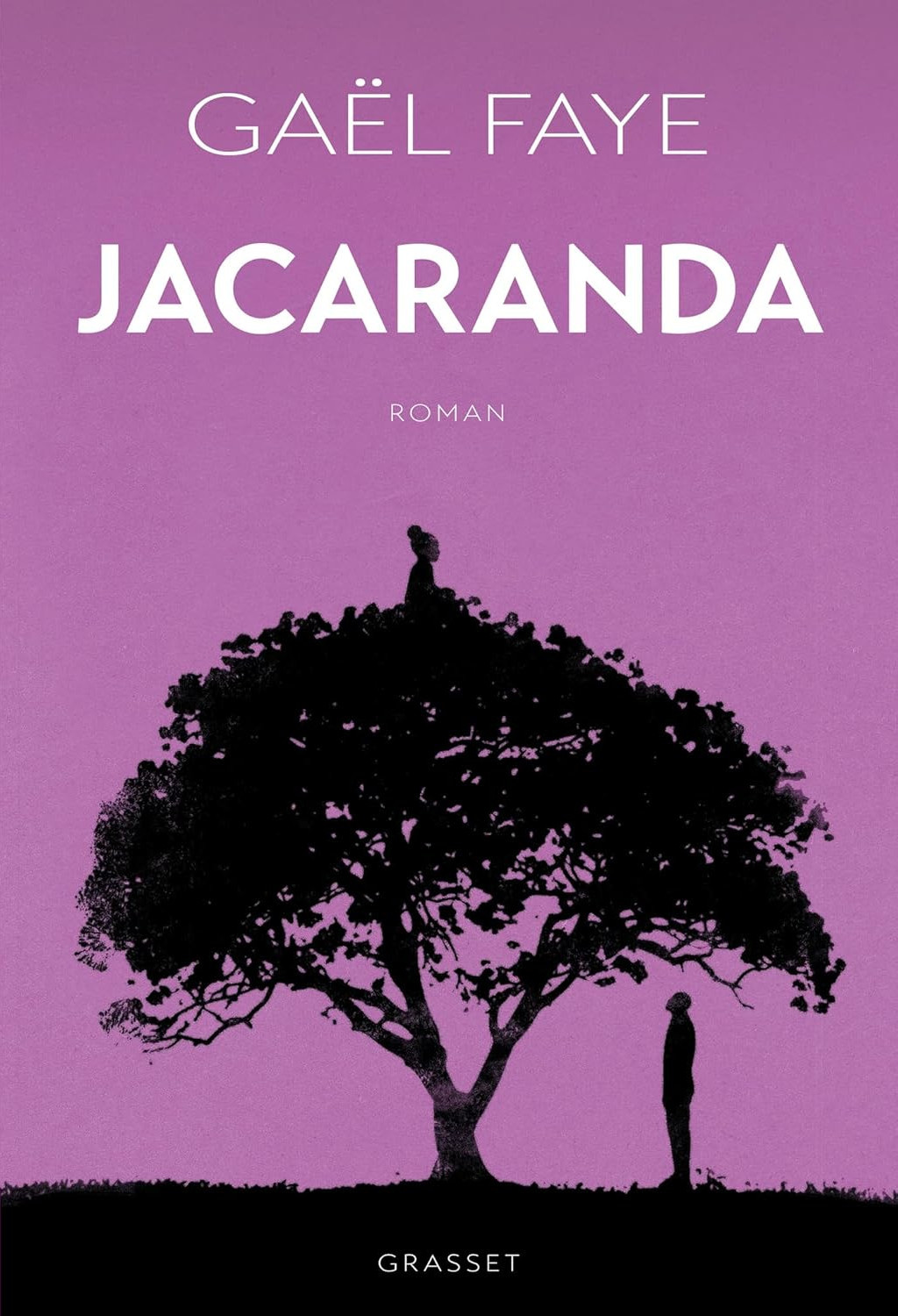

While Small Country was his first book, last year Gaël Faye published Jacaranda, a book that tells the story of Rwanda through the eyes of four generations of a Rwandan family and explores similar concepts. In a recent interview, Gaël Faye spoke of the precursors to genocide, the role the media plays in perpetuating stereotypes that dehumanize and justify the unjustifiable, and the question of whether perpetrators can be forgiven.

It’s a pattern we have seen throughout history and even today — in the Congo, in Palestine, in Sudan, in Myanmar, in Kashmir and Ukraine — of a perpetual justification of massacres and violence. And even worse, the playbook of, as Faye says, “removing the humanity to accept the deaths” - equating human beings to pests, cockroaches, and animals in order to downplay their murder - adds a new level of evil to already horrifying acts. As the son of a Rwandan refugee who grew up in Burundi, Faye has firsthand knowledge of the devastating effects of this rhetoric.

In 2020, Small Country was made into a movie, which I strongly recommend watching in lieu of reading the book for those that might not have the time.

Finally, in a part of the book that stood out as a source of hope and wonder, Gabriel strikes up a friendship with an old Greek woman who lives on his street. She introduces him to books that go on to serve as the only source of comfort for a child navigating a changing landscape. Madame Econompoulos describes books as “the great loves of [her] life,” encouraging him to read and explore.

“Thanks to my reading, I had broken free from the limits of our street and was able to breathe again; the world seemed bigger now… I discovered that I could talk about all sorts of things buried inside me that I’d been unaware of before.”

He’d read stories from around the world, noting how he felt he could have written the same stories. A connection that brings to mind a quote by one of my favourite authors, James Baldwin. In it he says, “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.” How true that is for all who try to make sense of their respective struggles in this world.

Quotes:

“There’s the fear of buried truths, of nightmares left on the threshold of my native land.”

“For privileged children like us, who lived in the city center and in residential neighborhoods, war was just a word.”

“What’s set to happen here will be far worse than any war.”

“His grief outweighed his reason…”

“In another time and another place, I’d have mistaken them for shooting stars.”

“My dreams were fettered by reality.”

“I sway between two shores, and this is the disease of my soul.”

Further reading: How Europe Underdeveloped Africa by Walter Rodney, The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon

He recently released Jacaranda, about the Rwandan genocide told by four generations of Rwandans.

UN Resolution 1017 (XI)

UNAMIR was a monumental failure.

Ndadye was then assassinated, followed by Cyprien Ntaryamira, who was then assassinated with the Rwandan president, an event that set off the 100 days of genocide in Rwanda.

Great Context! Sounds like a tough read.

These posts are so informative - thank you for sharing this perspective!